Santiago dune and wetlands

Picture: Miguel Angel Muguerza

As Urola river flows into the sea, a large sand and silt bank is formed on its right bank. To the north of this bank, a large dune is formed opposite the Bay of Biscay, and in the shelter of the bay lie the wetland marshes.

The geological materials found here range from the Upper Cretaceous (around 75 million years ago), with limestone and marl, to the Lower Eocene (around 55 million years ago), with sandstone, clay and marlaceous lime. The transition from the Cretaceous to the Tertiary periods is marked by limestone and marl with reddish layers, the result of heavy iron oxide sedimentation.

Over the limestone and marl substrate of the Upper Cretaceous lies the sand bank and silt formed during the Quaternary Period. These sediments today make up the beach and wetland area, and in some places are up to 30 metres thick.

The beach and wetlands contain a wide range of different vegetation, in accordance with their diverse environmental conditions.

The beach (Dune)

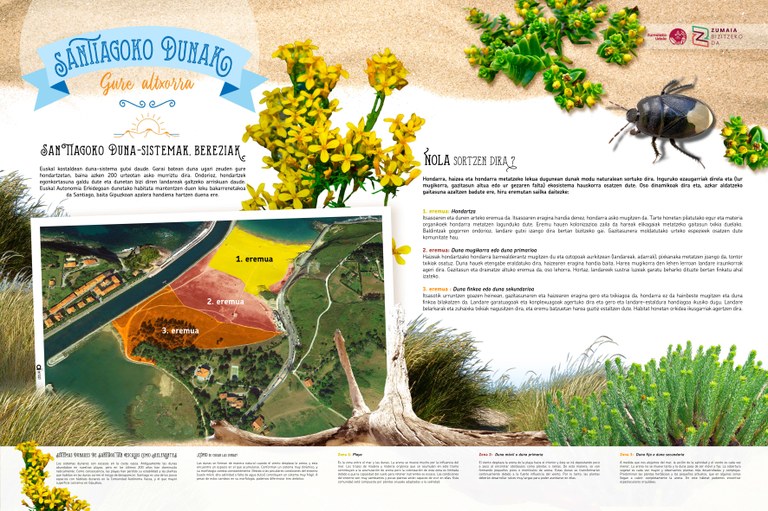

The dune begins at the highest area of Santiago beach, where the vegetation grows in broad strips, depending on the greater or lesser need of the different species to seek shelter from the drying influence of the sea, its salt residue and the wind.

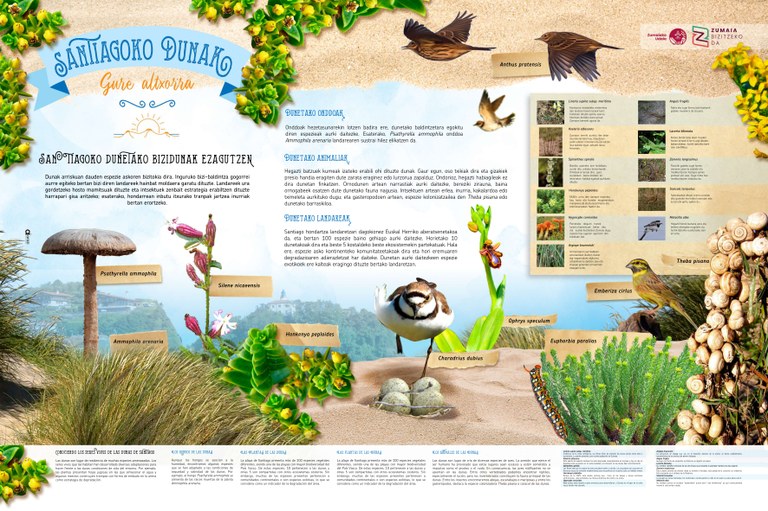

The plants that grow on the border between the beach and the dune engage in a permanent struggle with the tide and wind in order to carve out their niche. As a result, vegetable cover is scarce, and normally consists of annual, quick-growing species.

A little further back are the small hills formed by mobile dunes, created by the sand deposited there by the wind and waves. These dunes host a series of vivid plants which develop long runner systems to anchor them into the sand.

Behind these moving hills are the so-called grey dunes, which are more stable and are covered with a denser layer of plant life. Here, the environmental conditions are less harsh, since the sea is further away and the rain tends to wash the salt residue down to lower layers. Together, runner or crawler species, communities of annual plants, naked sandy surfaces and maritime pine trees form beautiful mosaics over the grey dunes.

In the area next to the Zuloaga house and grounds, which lies almost completely outside the sea’s sphere of influence, you can find a number of different bushes and several trees.

Despite being fairly small (3 hectares), Santiago beach is nevertheless an extremely popular place for leisure and recreational purposes, a circumstance which often results in the invasion of plants not originally part of the area’s ecosystem. Nevertheless, its population of flowering plants is particularly diverse, with 49 different species, including several fungi.

The garden of the Zuloaga house-museum is dominated by its many trees (mainly pines and cypresses), although the dune grasses have also been very well preserved in several areas.

The area’s animal wildlife mainly consists of invertebrates, with the most common groups being insects, spiders and gastropods. Vertebrates include several species of bird which either nest in the nearby trees or simply stop to rest here while migrating. Many years ago, the area also played host to a large number of green lizards.

1. ¿Como se crean las dunas? 2. Conociendo los seres vivos de las dunas de Santiago 3. Conservemos nuestros tesoros

The wetlands

The wetlands lie in a flat area of fine sedimentation which stretches several kilometres along the Urola estuary, creating a unique, very special landscape. The water of this ecosystem is fairly cloudy due to the suspended materials brought in by both the river and the sea.

Due to the influence of the tides, the vegetation is highly specialised and grows in broad bands in accordance with its tolerance to submersion. Thus, in the lower areas, the only plant life is green alga, which grows on a soft, non-solid substrate.

Those areas which are often flooded at high tide and are mainly silty in nature are covered in grass species, whose roots fix and elevate the substrate, thus enabling new sediments to be deposited.

Over this more elevated substrate there is a third band of vegetation formed by typical wetland plants, which thrive in a wet, salt-rich environment supplied with soil-based nutrients by the river. The vegetation is dominated by halophile (salt-loving) plants whose composition nevertheless varies, with the most tolerant being located nearest the sea, and the more sensitive growing further back.

The River Urola has two closely connected areas which are popular with birds: the Santiago zone and the area around Bedua. Over 100 different bird species have been observed in relation to the wetlands.

The number of birds in the area is always highest during the migration period. Spring is the season in which birds flock to the estuary in the highest numbers, although it is during autumn that they stay longest in the area. During this season it is not unusual to see flocks of waders such as sandpipers, lapwings, plovers, godwits and redshanks.

The area only has a few species of ducks, although mallards and northern shovelers can often be seen, among others. Several more spectacular and in some cases endangered species can also be observed, including the spoonbill, barnacle goose and purple heron. Every year, ospreys also make an appearance. They generally tend to prefer the Bedua region, although they sometimes visit the Santiago wetland in search of food.

During the winter, the number of bird species drops. Those that remain here during the colder months are relatively common, such as the herring, laughing and yellow-legged gulls, the red-wacked sandpiper, the ringed plover and the great cormorant. The little egret and the grey heron also stay, usually choosing to winter in Bedua.

Species which spend the winter on the open sea and suffer greatly during severe storms also find refuge in the estuary. The Urola therefore provides shelter to birds such as the artic skua, the common scoter, the razorbill and the guillemot.

During the summer months, only a few species remain in the wetlands; these include the pied wagtail, the grey wagtail, the common sandpiper and young yellow-legged and laughing gulls. Two nest-building species are particularly noteworthy: mallards, which often lay their eggs in the Zuloaga house-museum, and little ringed plovers, which raise their chicks in the Bedua area.

turismoa@zumaia.eus

turismoa@zumaia.eus

Bulegoa

Bulegoa