History

Although there are many unanswered questions regarding certain aspects of the origins of Zumaia, all historians coincide in that the town grew up around the Santa María Monastery which, in the year 1292, had been donated to the Roncesvalles Monastery by the King of Castille, Don Sancho IV, as stated by the earliest records which contain a reference to the place known as "Zumaya".

Despite different opinions regarding the exact location of the monastery, there is no doubt that the monks living there witnessed first-hand the birth of the town. Sick of continuous pirate raids and pillaging, those living scattered around the Sehatz valley decided to abandon their houses and build a walled, fortified settlement from where they could defend themselves, as a group, against their enemies. Zumaia was the site chosen for this purpose, among other reasons because of its size, strategic location and direct contact with the sea. However, the town did not legally become a villa or borough until 1347, when King Alfonso XI granted it a charter naming it “Villa de Villagrana de Zumaya” and bestowing on it all the rights and privileges enjoyed by the fuero (official set of local laws and liberties) of Donostia.

As regards the meaning of the name “Zumaia”, an often defended theory holds that it comes from the Basque term “zuma” or “zume”, meaning osier, a plant which was apparently fairly common in the region. As for Villagrana, some believe the name stems from the term “grana” or cochineal, produced at the time by the abundant oak groves.

By the 16th century, Zumaia had 136 houses, 70 lining the six streets which existed within the walled precinct and the remaining 66 scattered around the three districts or neighbourhoods located outside. The town had a total of 108 established surnames, 53 of which were of noble status. Today, no traces remain of the original walls which once completely encircled the town, broken only by those few stately homes and towers capable of fulfilling the same defensive function. The gateways, including the town’s main gate and the large cross which stood over the top, were destroyed during the middle of the 18th century in order "to make more space". The only natural gateway, i.e. that formed by the sea itself, would have been the most dangerous, since it was the most accessible.

From the 16th century onwards, the metal bells of the parish church have been melted down many times. It has been a while now since the old church bell was replaced. It was this bell that, in 1578, the mayor ordered to be rung six times, three times in a row, in order to inform the townsfolk and encourage them to attend the town meetings more assiduously. Nowadays, municipal meetings and events no longer begin with the traditional opening: “Here we meet to the peal of bells…”; no longer are two holm oaks felled, as they once were, on the eve of the Juntas Generales (Provincial Meetings which were held in the town once every 18 years) “to offer firewood and coal to the secretary of the province”. What has not changed, however, is the decision made during one of these meetings, specifically that held on 27 December 1620, the same day as Saint Ignatius Loyola was elected patron saint of Guipúzcoa, to name the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin Mary the patron saint of Zumaia. The years, or rather centuries, have obviously brought many changes to the old municipal bylaws (written in 1584), the urban development of the town itself and the customs and lifestyle of its inhabitants. However, it is the predominant economic activity of each different period which holds the key to charting the development of the town from its foundation to the modern day.

From the 16th century onwards, the metal bells of the parish church have been melted down many times. It has been a while now since the old church bell was replaced. It was this bell that, in 1578, the mayor ordered to be rung six times, three times in a row, in order to inform the townsfolk and encourage them to attend the town meetings more assiduously. Nowadays, municipal meetings and events no longer begin with the traditional opening: “Here we meet to the peal of bells…”; no longer are two holm oaks felled, as they once were, on the eve of the Juntas Generales (Provincial Meetings which were held in the town once every 18 years) “to offer firewood and coal to the secretary of the province”. What has not changed, however, is the decision made during one of these meetings, specifically that held on 27 December 1620, the same day as Saint Ignatius Loyola was elected patron saint of Guipúzcoa, to name the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin Mary the patron saint of Zumaia. The years, or rather centuries, have obviously brought many changes to the old municipal bylaws (written in 1584), the urban development of the town itself and the customs and lifestyle of its inhabitants. However, it is the predominant economic activity of each different period which holds the key to charting the development of the town from its foundation to the modern day.

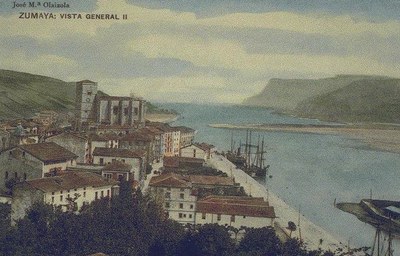

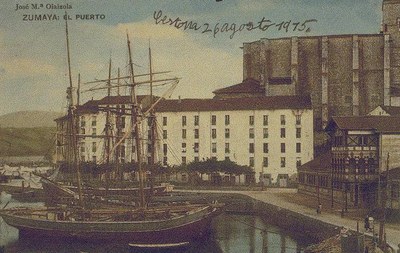

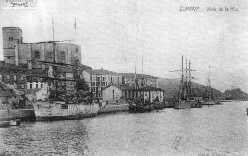

The majority of the first inhabitants of Zumaia were crop farmers, although the fact that they settled within close proximity of each other soon prompted the appearance of other professional and industrial activities. By the end of the 14th century, the townsfolk were already building ships in the estuary. A large percentage of the population were either fishermen or sailors. At that time, the estuary was a rich fishing ground containing a large number of different species, including salmon, trout, shellfish and eels. Many people combined coastal fishing with farming, although cement production also became a major industry, with the townsfolk making use of materials from other sites in the surrounding area. Goods were shipped from the port to the Netherlands and manufactured products were imported. There is even one historian who claims that a passenger boat which linked the town with Santiago Chapel, a common stopping point for pilgrims on their way to Santiago de Compostela, was one of Zumaia’s most important sources of income during the 16th century.

The majority of the first inhabitants of Zumaia were crop farmers, although the fact that they settled within close proximity of each other soon prompted the appearance of other professional and industrial activities. By the end of the 14th century, the townsfolk were already building ships in the estuary. A large percentage of the population were either fishermen or sailors. At that time, the estuary was a rich fishing ground containing a large number of different species, including salmon, trout, shellfish and eels. Many people combined coastal fishing with farming, although cement production also became a major industry, with the townsfolk making use of materials from other sites in the surrounding area. Goods were shipped from the port to the Netherlands and manufactured products were imported. There is even one historian who claims that a passenger boat which linked the town with Santiago Chapel, a common stopping point for pilgrims on their way to Santiago de Compostela, was one of Zumaia’s most important sources of income during the 16th century.

During the two following centuries, the 17th and 18th, the town's history was somewhat less resplendent. Farming remained the main economic activity for the majority of inhabitants, despite the fact that Zumaia continued to suffer from an agricultural deficit, especially as regards the production of wheat, corn and beans. At one point things became so bad that in 1766, all the houses in the town were searched in order to check that no one was hoarding more grain than they required for their own nourishment and survival. Some townsfolk continued to transport goods (mainly iron) by both land and sea, and the fishing industry must have thrived since a couple of years prior to 1610, the San Telmo Mariners' Guild was established.

It was during this period, however, that emigration increased. The exodus began at the end of the 16th century (in 1616, Zumaia had 935 inhabitants) and did not cease until the economic resurgence two hundred years later.

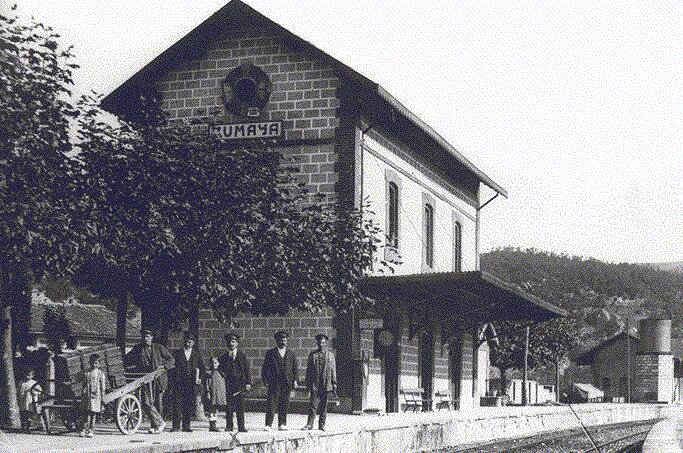

The situation began to improve towards the very end of the 17th century, among other reasons because the draining of the coastal wetlands enabled the old reed beds to be turned into farming land, thus increasing the town's agricultural yield, especially as regards corn. However, this was not the only factor that contributed to the aforementioned economic resurgence. In the 19th century, the local cement factories became the driving force behind the town’s economy, and helped also to boost the port's commercial activities. Land transport also improved during this period, since between 1882 and 1885 the road linking Zumaia to Getaria (and so Donostia-San Sebastián) was built, in 1900 the train connecting Deba and Zarautz was completed and in 1926, the Urola railway line (now no longer running) was inaugurated. These better communications, however, proved fatal to Bedua port, whose commercial activities floundered as a result of the Urola bridge, which prevented boats from sailing upriver.

The situation began to improve towards the very end of the 17th century, among other reasons because the draining of the coastal wetlands enabled the old reed beds to be turned into farming land, thus increasing the town's agricultural yield, especially as regards corn. However, this was not the only factor that contributed to the aforementioned economic resurgence. In the 19th century, the local cement factories became the driving force behind the town’s economy, and helped also to boost the port's commercial activities. Land transport also improved during this period, since between 1882 and 1885 the road linking Zumaia to Getaria (and so Donostia-San Sebastián) was built, in 1900 the train connecting Deba and Zarautz was completed and in 1926, the Urola railway line (now no longer running) was inaugurated. These better communications, however, proved fatal to Bedua port, whose commercial activities floundered as a result of the Urola bridge, which prevented boats from sailing upriver.

The cement industry began to decline at the beginning of the 20th century, around the same time as the shipbuilding industry revived, followed shortly by the advent of the motor industry. Here it is worth noting that it was a firm based in Zumaia, Yeregui Hermanos, which assembled the first diesel engine in the whole of Spain. This industrial boom resulted in a notable increase in the town’s population, mainly due to immigration.

The weighting of the different activities driving Zumaia's economy had changed substantially by the beginning of the last century: in 1950, 56.1% of the population worked in industry, while only 17% were employed in the agricultural sector. Years later, the recession hit Zumaia, aggravated at times by workforce restructuring and even the closure of some large companies which had hitherto been cornerstones of the town's economic prosperity. Today, nearly fifty years on, at the threshold of the 21st century and following the establishment of various more modest firms which are better aligned with the new economic trends of the market, the percentages are generally in keeping with the (somewhat critical) economic situation prevalent in the local region.

turismoa@zumaia.eus

turismoa@zumaia.eus

Bulegoa

Bulegoa